THIRTY years ago I was working in my first job in journalism on the Craven Herald & Pioneer in Skipton and saw an advert asking for submissions for a book featuring fiction from writers based in Yorkshire.

The work below had already been written. Mirrors of Apathy was grim, dour, nasty and spiteful, but was nevertheless selected for inclusion by Suzi Blair, the editor of “paper clips” — the lower case title always annoyed me.

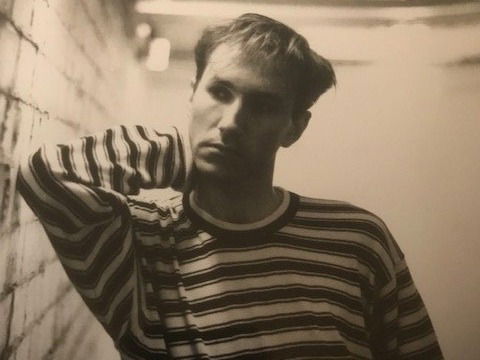

My dad’s brother Malcolm wasn’t happy with the content of the ensuing publicity in the Craven Herald. Alongside the picture on this page which staff photographer Stephen Garnett took in an underpass at Skipton railway station — making me look like a heroin addict according to my mum Jean — I talked about my character’s disdain for trainspotters. Malcolm was one. Harsh, I know.

Reading it again between pages 147 and 151 of “paper clips” the story is notable, among other failings, for its total lack of dialogue. Some of the wording now appears so dated ("dork!") as to make me laugh — and I wrote it. My girlfriend at the time said it captured the zeitgeist. She was being very generous.

Still, I was so proud to see it in the Craven Herald book shop beneath our office on Skipton High Street, though I’m not sure anyone bought it.

Here it is:

MIRRORS OF APATHY by ANDREW J MOSLEY

JUST one hour ago Skeggs had been sitting at the table of his small untidy Keighley bedsit, eating toast and sipping tea while scanning a copy of a Monday broadsheet, just like he did every morning before setting off on the monotonous journey to the daily grind. But now he had killed.

He’d been sick of safety and stability and pissed off with the permanent for some time now. And this particularly murky Monday morning had made his mind up.

He had it better than some though, that much was obvious, and he wanted to help. He wanted to help just one person not to have a better life but the perfect death. Bing Crosby had died on the golf course and Tommy Cooper on stage both doing what they loved to do where they loved to be, so why couldn’t this happen to an ordinary Joe?

Skeggs’ work bag generally contained his lunchbox, paper, pen and a few textbooks placed there for effect — Christ the life of a trainee clerk was bloody uninspiring — but today it housed an extra item. And it was loaded.

He walked the short distance to the train station, the light rain settling on his thick black hair, and reached the platform at 8.12. In the minutes before his train arrived, five minutes late but five minutes earlier than usual, a thousand thoughts flashed through his mind. He thought about the uselessness of his ordered life and the uselessness of the lives of the rest of the paltry crew assembled on the windswept platform. He thought about the pointless existence of the train driver, who arrived at the end of a day’s work in the exact place he had set off from and he thought about the ridiculous days of the countless pigeons plodding about in the platform’s puddles. But most of all he thought about the sad state of his victim, his victim’s family and everyone his victim knew.

Skeggs boarded the train, found a rare vacant seat and settled down for what would normally be a 45 minute journey to tedium. He surveyed the rest of the Leeds-bound crew and decided that at 24 he was somewhat younger than the majority of them, but equally down. Everyone stared straight ahead, emotionless, and everyone seemed to be staring straight at Skeggs. The fat man in the ill-fitting pinstripe suit, the unshaven builder in the red bobble hat, the accountant with the beard and bald head and the man peering over his copy of The Times, briefcase on lap; they all stared at him. Did they know?

Skeggs began to sweat. As he did so he nervously ran his fingers through his hair and his slight frame began to shake uncontrollably. He felt for the shape of the gun which was positioned at the top of his bag. No, they couldn’t know.

Nobody on the train showed any interest in any of the other passengers and nobody spoke. This was because none of them had anything remotely inspiring to say about themselves, Skeggs thought to himself.

Where were all the heroes? All these people and their existences were so shallow, so pointless. What was their worth? Why were they alive? Were they alive even?

Skeggs turned his thoughts to his victim. New Age travellers, religions and races, punk rockers, hipsters and Jeremy Beadle all provoked unwanted derision from large proportions of Britain’s downtrodden population, but none quite as universal as this dedicated follower of anti-fashion. Hell, you might not like football or cricket but you didn’t object to people playing it. And you might detest whisky or brandy, but you didn’t mind others drinking it. But if you didn’t like what this person did you sure as hell didn’t like him. Crazes come, crazes go and fads fade out, but this one had outlived everything from hula hoops to skateboarding. Skeggs was going to make sure though, that within the next half hour there was going to be one less partaker in this particular activity.

He smiled nervously to himself. The journey was halfway over now and the endless fields disappeared into the background. Skeggs’ heart skipped countless beats as he grew angrier inside. His anger was directed at this particular person whose very existence screamed "it is 1993 and I have nothing to say, nothing worthwhile to do and no money to do it with".

Every time Skeggs saw this person his mouth contorted itself into an involuntary sneer and he had to fight desperately hard to suppress a cry of "get a f******g life, dork".

Britain 1993 meant unemployment, homelessness, AIDS, teenagers on crack and an overriding sense of apathy that this person more than any other to Skeggs reflected. His fascination was Skeggs’ hate and the very things that meant to Skeggs scummy people, scummy food and scummy lives. Thank God he was nearing his destination now.

The train was packed solid. An extremely unpleasant fat balding man with a self satisfied smirk seemingly a permanent figure on his flabby face had positioned himself next to Skeggs and as his hate intensified he ran his fingers along the outline of the gun, the temptation to use a bullet on the man becoming overwhelming. But no, that would be a pointless murder and a pointless reason to spend the rest of your life in prison for. The image conjured up by the thought of prison made him shudder slightly, but he wasn’t going to be put off that easily.

As the train approached Leeds Station, Skeggs rose from his seat, pushed his way past his unwelcome neighbour and made his way towards the exit. Trains pulled in, trains pulled out and trains remained stationary.

As commuters in boring grey suits and shiny shoes, carrying black briefcases, rushed towards the station’s exit and another day in the office, he saw one, then another. Suddenly they were all over, not moving, not speaking, but there.

Yes, his victim was among them all right, blue anorak pulled right up to the top to keep out the bitter April chill, hood forward masking his face, grey trousers flapping in the wind as he tentatively paced the hard grey surface of the platform in his scuffed brown laced-up shoes.

You look just the same as the rest of them. They all look the same, Skeggs thought. His heartbeat quickened and his watch appeared to start ticking faster than time passed by. Then, action.

A hand appeared from within a long blue sleeve of a snorkel jacket and carefully drew a neat black biro line over a long number in a small book and the other hand pointed a cheap-looking camera at the uninspiring two carriage sprinter that slowly but abruptly drew to a halt in the station.

Skeggs stepped off the train and let his hand grip the shiny black weapon. With unemployment on a never-ending spiral, the working class priced out of football and new fascinations such as Sega and Nintendo machines way too expensive for the average family, the sort of activity Skeggs wanted to destroy mirrored the apathy fell by the majority of Britain.

Activities such as this were in the ascendance because there was simply nothing else to do.

See a city, any city and see a million pleading faces, a million broken hearts and a million dreams ripped apart, chewed up and spat out as nightmares. See a million forgotten souls in a thousand forgotten towns and you see these people.

Yes, the defeated broken-backed classes of Britain are that desperate, Skeggs thought as he stepped down on to the platform, turned the corner and walked slowly towards a clutch of people huddled together. One of them would be his victim. Yes, he was there.

Skeggs’ pace quickened, and he grimaced as he caught sight of the resigned expressions on the long faces pressed against the dirt-covered windows of the works special, from which he had just disembarked. The British obsession with work. Lots of time spent doing it but nothing ever done.

The unsuspecting victim was bent down, placing his biro and notebook into a plastic Littlewoods carrier bag. As Skeggs move towards him, he looked up from the bag and his mouth worked its way into a warm, welcoming smile. His face was barely able to hide the pleasure he so obviously felt as he pointed his flash gun at the 8.20 works special. Skeggs in turn pointed his gun and both prepared to shoot.