I CAN'T really decide. If I don't it will just be further delayed but if I do there will be the inevitable disappointment that I didn't have a go and get it out to publishers. You know, just to see.

I need to move on though. I've been living with Michael Morrison, the main character in The Choreography of Ghosts, in my head for almost a decade now. Sometimes he's disappeared for long periods of time, but he's always returned.

He's a changed man now, less bitter than when I penned the words below so many years ago. He's a more rounded character, a better conversationalist and isn't blaming the world for what he perceives as his failures.

Michael's life, since his move from Yorkshire to the Amalfi coast, hasn't exactly been a bed of pizza, piazzas, pasta, sea and beauty, but he's in a healthier place than he was when these words were written. And when I say I've been living with him in my head... actually, I think I was him/him me.

He's different now. Better. So is the book. Otherwise I wouldn't even be considering pressing the 'publish now' button after ten drafts.

I've just about finished formatting The Choreography Of Ghosts on AmazonKDP - an e-book or physical too? I just need to ensure I've not messed it up, get a cover done, then set a date to publish. Or do I?

Whatever, this was left on the cutting room floor along with 30,000 or so other words.

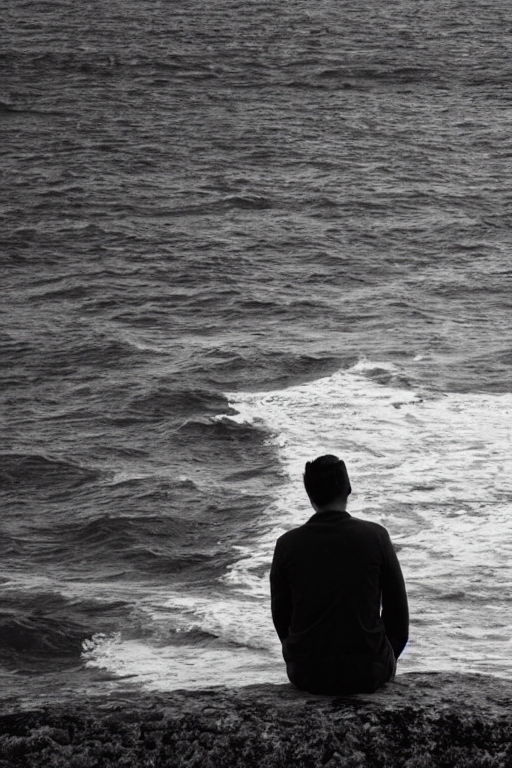

MORRISON had twice tried to remove himself from the world, or maybe the world from him. It was never really about hating himself, more a fear of the future, the situation he was in and was going to be in, not seeing any potential for a better path. And on days like today he could only conclude that he was absolutely, totally, completely bloody right.

All of us in this situation have had years of hauling ourselves out of bed to sit in traffic, queuing to get to somewhere we don’t want to be with people we don’t want to be with just to earn what is commonly referred to as a living. Earning a living but not a life. Wondering if this is it, wondering whether or not it will ever get any better, still wondering at 40, 50, 60 and 70 and then knowing. Knowing that yes, that was it. That was life.

Feeling bad because you know there are literally millions, thousands of millions of people worse off than you in so many ways and dealing with it, coping with it, like people do because they have to. If you can’t dig yourself out of your hole, what are the options?

Morrison spent far too long in his flat thinking this way. This had been one of those days: bleaker than the North Yorkshire Moors, Wuthering Heights bleak in fact, but without the hope that the words gave the Brontes.

He had the words, it was just that they were in the wrong order. Everything was in the wrong order and he couldn’t make sense of the madness, the sadness, maybe a mixture of both. Even if he could make the words powerful, they didn’t actually give him the means to change anything. He would write though. He would try to write. Give it a go. Write himself out of this mess.

But he needed discipline, discipline and targets. He would set them and break them. Ill-discipline and alcohol. Ill-discipline, alcohol and excuses. Excuses and anger. Anger and jealousy. Jealousy and hate. Just hate. So much hate. Where had the love gone? Was it ever there?

He would walk into book shops and stare at the racks of fiction. Walk round, head on one side, reading the spines with authors’ names on them from A to Z. How many of them were born into money? Money doesn’t buy you talent but it buys you the time to develop your skill. All these writers, sons and daughters of other writers, sons and daughters of successful business people, sons and daughters of TV personalities, pop and film stars, can afford the time. Like posh comedians or musicians whose parents give them a year or two to make it big before, in the event of failure, they fall, jump or are pushed into the safety net of the family firm.

He would write down the names of the books he thought looked good, then go back to his flat and Google the authors, find out what he could about their backgrounds and rage at those he perceived to have been handed the roll of the dice on a very expensive plate. He couldn’t help it even though he knew the anger and jealousy were destroying him.

Being a journalist had been an ambition way beyond what he believed possible for himself and now, having worked for more than 20 years in the industry with any God’s amount of chancers, some complete and utter idiots, shallow as shit, that seemed ridiculous.

That lack of confidence was his mistake and it was this mistake that had haunted him through life, a life ongoing because he happened to have drunk so much both times he tried to end it that the pills did not stay inside him for long enough and on all other occasions when the prospect of ending it had occurred to him he had thought of something good coming up in the near future that seemed to make it worthwhile continuing for a while longer.

On better days, interviewing interesting people, decent people, people with a story to tell, people who had overcome sadness, badness and adversity, when the banter in the office was good and he had gone out for drinks with colleagues afterwards, he enjoyed the job. Enjoyed his life even. Briefly.

Back behind closed doors it was just a job, any job and all hope of ever completing anything worthwhile outside of the walls of the office in which he spent around a third of his day, every day — even weekends sometimes — was eroding at real speed. In fact, and sometimes he wished this had been the case, it nearly finished before it started.